|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table of Contents A. Introduction -- MI 9 and Clayton Hutton G. Money Purses and Map Pouches I. D Survey Assumes Responsibility for Escape Maps

A. Introduction -- MI 9 and Clayton Hutton The history of the production of cloth maps by the British during World War II begins with the story of Clayton Hutton, an Englishman who was a pilot in the Royal Air Force during World War I. He was not a career military man, but instead had lived a rather varied and colorful life with experience in journalism as an employee of the Daily Chronicle, followed by a stint as a publicity director in the film industry. Upon the eve of Britain's entrance into World War II, Hutton was determined to serve in the uniform of his country again. He applied for service in the Royal Air Force but was rejected. He managed, however, with great persistence to land a job as an British Army intelligence officer in 1939.

Clayton Hutton

As Hutton relates in his wartime memoirs, Official Secrets,[1] it was not a vast background in intelligence matters that accounted for his acquiring this position, as he had no such experience, rather it was his fascination with magicians, illusionists and escapologists, and, more specifically, an attempt to outwit Harry Houdini. While working in his uncle's timber mill in 1913, Hutton was intrigued by a challenge issued by Houdini agreeing to reward one hundred English pounds to anyone who could construct a wooden box from which Houdini could not escape. Hutton accepted the challenge with Houdini imposing only one condition: Houdini be introduced to the carpenter who could make such a box. Hutton agreed and introduced Houdini to the carpenter during Houdini's visit to the timber mill. The box was constructed, and one night during a performance at the Birmingham Empire theater, Houdini effortlessly escaped from the box resulting in Hutton immediately losing the challenge. Only years later did Hutton learn that Houdini had bribed the carpenter three English pounds to nail one end of the box with two full length nails while the other seemingly identical nails were much smaller and penetrated only a single thickness of planking. This allowed Houdini to easily kick out the box end, escape from the box, and quickly hammer it with proper nails under the cover of the toning of a Sousa march before reappearing to the audience from behind a small curtain placed around the box on stage.[2] When Hutton shared this Houdini story during his job interview with Major (later Brigadier) Norman Crockatt, the head of the British military intelligence escape and evasion service, known as MI 9, Hutton was hired on the spot.[3] MI 9 had been officially established in December 1939;[4] it's mission being to facilitate British evaders whose aircraft were downed in enemy occupied territory and to assist British prisoners of war in escaping from German POW camps.

Brigadier Norma Crockatt

Impressed with the functions of the British MI 9, US Secretary of War Henry L. Stinson established on October 6, 1942, MIS-X, a branch of the Military Intelligence Service of the US War Department, to perform like functions for US forces.[5] MI 9 and MIS-X worked closely and quite effectively with minimal rivalries in all geographic regions, both nations agreeing that MI 9 would have lead responsibility for escape and evasions activities in Europe[6] (including the in the Mediterranean), North Africa,[7] the Middle East,[8] India,[9] Burma,[10] Thailand,[11] and Malay,[12] while MIS-X having primary responsibility in North and South America,[13] Australia,[14] New Zealand,[15] the Pacific,[16] China,[17]Japan,[18] Siberia,[19] and French Indo-China[20]. MI 9 was responsible for the following escape and evasion activities: (1) Briefing British military personnel (primarily pilots) before departing for missions into enemy territory in the art of escape and evasion. (2) Establishing codes for clandestine communications with Allied POWs. (3) Interrogating successful evaders and escapees to obtain valuable intelligence, and (4) Developing and procuring tools, maps, and other aids to assist escapees and evaders and issuing those devices to military personnel before missions over enemy territory or smuggling the items into POW camps for use in prison escapes.[21] It was the latter endeavor that Lieutenant (later Major) Hutton was put in charge.[22] Contrary to experiences during of the First World War and partially because of the signing of the Geneva Convention in 1929 guarantying POWs human treatment, Allied service personnel were taught that it was their obligation to attempt to escape if captured. It was hoped that escapes would tie down enemy forces hunting down escapees, help return personnel with valuable flying experience to fly another day, and enhance POW morale from the boredom of daily prison life by giving POWs a sense they were still in the fight. Hutton's first task was to design and acquire maps that could be used by evaders and escapees. He unsuccessfully sought to obtain a copy of a small scale (1:2,000,000) map of Germany from the British War Department so in Spring 1940 he ventured unannounced to Bartholomew's, a famous Edinburgh mapmaking company, where he secured tourist maps of Germany, France, Poland, Italy, Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, Holland, and the Balkans. When he expressed his intention to print thousands of copies of the maps, the proprietor dismissed outright the notion of any remuneration for the use of the copyrighted maps, insisting that it was a privilege to contribute to the war effort.[23] Obtaining the maps proved fairly easy; however, identifying a suitable material on which to print the maps proved more difficult. Hutton sought a material that was thin enough not to take up much space, light weight, while also being fairly durable and crease resistant, and finally because the maps would be used behind enemy lines they had to be silent when unfolded rather than making the usual rustle noise of the unfolding of a paper map. He experimented with various tissue papers for a few days, but quickly realized they were unsatisfactory. They rustled noisily and the information along the creases was illegible after the maps were folded for a few hours. He concluded that the only suitable material was silk. But, after experimenting with a printer acquaintance using eight ink colors on silk samples, his results were disappointing: each time the silk was lifted from the printing apparatus, the ink ran, blurring outlines and rendering place names illegible. Finally, by happenstance he mixed a little pectin with the ink and at once the pectin coagulated the ink and presented it from running. Now, even the smallest topographic features were sharply defined on the map.[24]

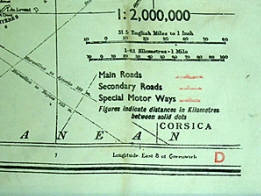

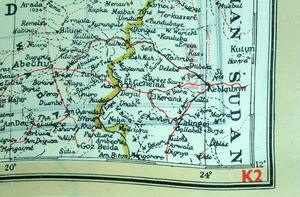

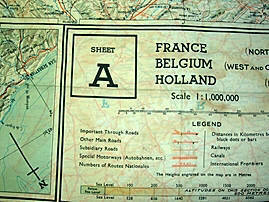

After securing several bales of silk parachute, the silk escape maps became a reality. The first maps produced were based on the Bartholomew maps.[25] The Bartholomew maps are rectangular in shape and were printed in three colors: map details in black, roads in red, and international boundaries in green, although some of the maps were printed solely in black on white cloth backgrounds. They are small scale and range from 1:1,000,000 to 1:6,000,000, each is undated. The scales of the maps were criticized by some personnel as being too small; however, MI 9 defended the maps as being intended only to give an escaper or evader an idea of the general direction in which to proceed.[26] Each map has a sheet identifier, usually consisting of an upper case letter that is sometimes followed by a number (for example, D or H2) in its southeast corner and often in at least one other corner. No defined numbering system was used; the numbering seems somewhat arbitrary or perhaps in some sequential order of production, but not a recognized accepted geographical numbering system. These early maps are recognized by their hemmed edges to prevent them from unraveling, while later Bartholomew maps used heat treated edges. Some of the maps are single sided, while others were printed with maps on both sides.

Bartholomew Map Corners

The maps were printed in large quantities; a conservative estimate is that over 400,000 of these maps were printed with over 70,000 copies alone of the double-sided silk map sheets of D and H2 being printed between July 1942 and August 1943. [27] A booklet produced by MI 9 in 1942 indicates as many as 71 different silk map sheets may have been printed up to that time.[28] (Click here for a list of the Bartholomew maps and sample photos.)

Hutton's memoirs reveal an impish decision by Hutton to classify the maps secret. Although identical Bartholomew cycling maps were on sale in numerous stores throughout the United Kingdom, Hutton chose to mark his initial silk maps "Most Secret." According to Hutton, one day two police detectives visited him investigating one of Hutton's silk maps of Germany marked Most Secret. One of the detectives had confiscated a silk map from a young RAF pilot in a pub after the detective saw the man take the map out of his pocket and hand it to his girlfriend who used it as a headscarf as they departed the pub. The detectives were rightfully concerned because of the Most Secret marking displayed on the map. Hutton took one of the detectives to a Fleet Street stationer?s store in which identical Bartholomew cycling maps were openly on display. Apparently, this cleared up the matter and the young flier was let off with a lecture regarding security mindfulness.[29] Perhaps because of this incident, subsequent maps no longer carried such a legend although they were still considered restricted items. Hutton also alleges that to maintain secrecy, he referred to his silk maps as "eggs and bacon" when he submitted his expense invoices to the Treasury for payment.[30] Even though the markings were changed and a large number of cloth maps were distributed during the war, MI 9 was quite possessive of its maps as the following reveals. In February 1945, the American Military Air Attach? in Madrid, Spain, requested that MIS-X send 50 copies of the British cloth map sheets K3 (Spain) and H2 (North Africa) for issue to the officers of the Spanish Air Force. MI 9 denied the request stating that it was MI 9 policy to issue the cloth escape maps only to British and American forces.[31]

Another series of British escape maps was printed on silk in 1942 at a scale of 1:100,000 consisting of 33 sheets that corresponded to the GSGS 4090 paper map series, produced by the UK Geographical Section of the General Staff (GSGS), of Norway extending just north of Oslo, adjacent to the Swedish border, and outside the area garrisoned by German troops. These sheets have heat sealed edges and are monochrome except for sheets 26B and 26D that were printed in four colors--black, red, brown and blue. These maps are purportedly quite scarce as it is reported that only 100 copies of each were produced.[32]

During the war, many British escape maps were printed on silk, quite often from silk rejected during the manufacture of parachutes. In fact, in the spring of 1944, the US shipped 1 million yards of slightly damaged parachute silk from New York warehouses to the British for use in making escape maps.[33] Nonetheless, because of the scarcity of silk, in 1943 the British also began using viscose rayon and cuprammonuium, a form of rayon commonly known as Bemberg silk or copper rayon. Rayon, unlike most man-made fibers is not synthetic but is made from wood pulp. The properties of viscous rayon and cuprammonium rayon are similar although they are made by different processes.

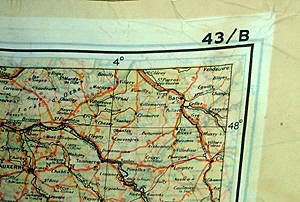

In 1943 another series of cloth escape maps were produced that are immediately recognized by their vivid colors. These maps are of the European Theater and were issued to Allied pilots of the US, RAF, and RCAF. Printed by the company of John Waddington, Ltd, the maps consist of eight colors and are primarily at a scale of 1:1,000,000 with larger scale inserts. There are ten sheets in this series, which are composites of various paper sheets of the then existing International Map of the World, unlike the previous escape maps which were exact copies of existing paper sheets. The sheets are numbered with the prefix 43 followed by one of the upper case letters: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, and K (east) and K (west). When all the maps are laid out they basically overlap to provide a complete map of Europe. The maps were usually printed on both sides, although single-side versions exist. Normally, the maps were printed sequentially--A on one side and B on the other side; C on one side and D on the other side--although that was not always the case. For example, maps with C on one side and E on the other side are also occasionally found. The maps can be identified by the following sample designations:

The 43 Map Series

An interesting feature of the maps is the black points on the map with corresponding distances between the points expressed in chilometers. For example, the distance would be marked indicating the distance between two large towns. This assisted the user in readily identifying distances without having to measure the distance with the scale legend printed elsewhere on the map. (Click here for a list of the 43 Series maps and sample photos.)

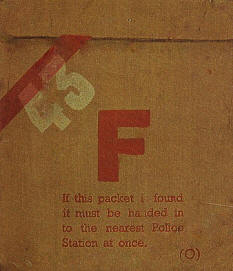

G. Money Purses and Map Pouches Allied aircrews operating in the European theater were issued silk maps packed in escape and evasion money purses. The purses were constructed of a brownish rubberized fabric sealed in a clear waterproof covering that kept their contents dry. The purses contained foreign currency of the countries over which the planes would be flying. The money was intended to help downed crewmembers in obtaining local assistance while attempting to return to friendly lines. Besides containing money and silk maps, each purse also contained a miniature brass compass and a small metal hacksaw blade. The purses themselves were secured shut with adhesive and were only to be opened if needed. As can be imagined, the purses were a closely accounted for item by all units because of the money they contained. The known purses issued during the war are described in the below table. [33a]

Money Purses Distributed to US Air Personnel thru 30 June 1945

As indicated in the above table, each purse was referred to by a color designation. The color designation was indicated by a diagonal line printed in the upper left corner on the front of each purse. Also printed on the front of each purse were capital letters representing the countries of the currency contained in the purse. For example, "F" for France and "I" for Italy. When the purses contained one color designation, normally the diagonal line and the country code was printed in the same color, whereas when the purse had a two-color designation, the diagonal line was the first color and the country code was printed in the second color. Of course, the color coding allowed easy identification of the purse's contents without having to open the purse. The above table also reveals that when the 43 series of maps were produced in 1943 those maps were substituted for the Bartholomew maps in the purses. Purses containing the 43 series maps had the number 43 printed in the upper left corner on the front of the purse.

Red 43 Money Purse

Late in the war (after February 1945) map pouches were issued to Allied aircrews, often in lieu of purses. The pouches were made from the same material as the purses and were roughly the same size, but were referred to in official records as map wallets. The front of the map pouches were often printed with "MAPS ONLY." Since the map pouches were distributed later in the war, they mostly contained the 43 series silk maps. The front of the pouches often identified the maps contained in the pouches, such as "C/D" and "E/F." Official records reveal that 7,500 "CDEF Map Wallets" were requested for issue to US Air Divisions. [33b]

Map Pouch with Escape Map, Compass and Hacksaw

Map purses are rarely available on the collectors market because the money purses were restricted items that were required to be turned in and the money accounted for. Map pouches are commonly found because they were declassified at the end of the war and individuals were allowed to retain them as souvenirs.

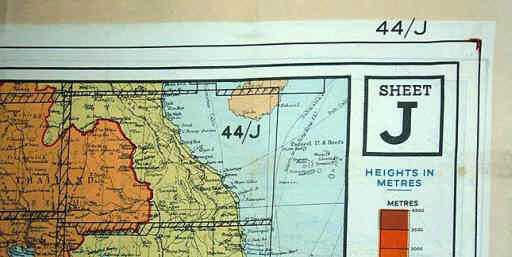

The MI 9 unit located in India was very impressed with the 43 series of Europe so MI 9 in London offered to produce a large number of similar cloth maps covering Southeast Asia.[34] Accordingly, in 1944, a like series of maps was produced with identical colors and scales. These were also composites of existing International Map of the World sheets. There are eight cloth map sheets each identified by the prefix 44 followed by an upper case letter: A thru H, J thru O, and R, S, V, and W. Reportedly, there were proof sheets for 44/T and 44/U, but they were never printed. The maps can be identified by the following sample designations:

The 44 Map Series

According to official records of E Group,[35] Southeast Asia and India Command, these cloth maps were packed inside money pursues issued to aircrews.[36] (Click here for a list of the 44 Series maps and sample photos.)

I. D Survey Assumes Responsibility for Escape Maps Prior to August 10, 1944, MI 9 arranged for the printing of cloth escape maps. After that date, D Survey assumed responsibility for the production of the British escape maps according to the requirements dictated by MI 9, including MI 9's arbitrary sheet numbering system, to which D Survey unsuccessfully objected.[37]

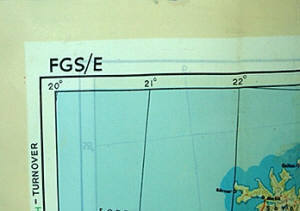

A smaller series of cloth maps was produced at a scale of 1:1,000,000 or 1:1,250,000 depicting the Scandinavian and Northern Europe region. The maps can be identified by the following sample designations:

FGS/E Map Corner

One double-sided map is identified with as FGS A/ E and contains inserts of areas B, C, & D. Another version of A/E contains maps A through E all by inserts. Other double-sided maps in the series include A/B, C/D and E/9.C.a. FSG appears to stand for Finland Sweden Germany. The colors and specifications for this series are very similar to the 43 and 44 series mentioned above. In fact, some FGS maps expressly state they overlap with the adjoining 43/C and 43/E maps. British cloth maps were not only used by Allied aircrews during WWII but also by special operatives such as Major William E. Colby, a US officer with the Office of Strategic Services (and later a director of the Central Intelligence Agency), who carried an FGS A/E map during Mission Rype in Norway during the spring of 1945. The purpose of the operation was to sabotage railways to prevent German troops from being shifted from Norway to Germany to confront the advancing Allied troops during the latter days of the war. (Click here for a list of the FGS maps and sample photos.)

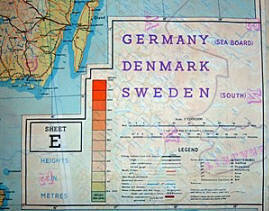

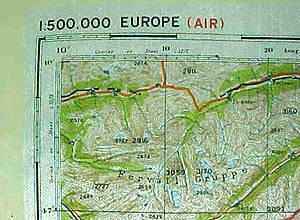

Some of the rarest WWII escape maps were the cloth copies of the Air Ministry GSGS 3982 paper series. Ten cloth maps were produced of the main Air Ministry series at a scale of approximately 1:2,500,000, while an additional 73 cloth maps were printed at a reduced size (13 in. x 15 in.) and with a scale of 1:500,000 scale. The latter are referred to as the ?miniatures.? Between July 1942 and July 1944, 34,000 copies of the miniatures were produced. The maps in his series are identified with a number followed by a capital letter and then sometimes followed by a lower case letter (such as 9U or 9.C.a). The miniatures are single sided and several of the main series are double sided.[38] The maps can be identified by the following sample designations:

GSGS 3982 Series Map Corner Map Corner

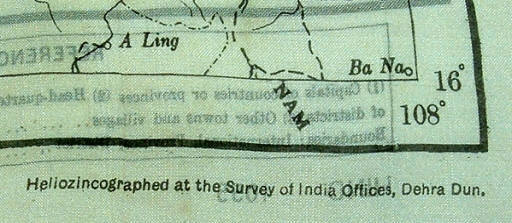

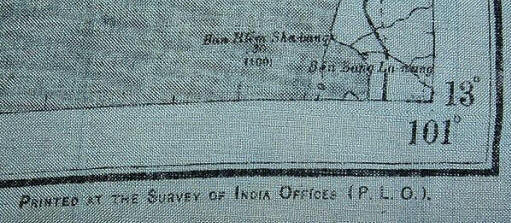

The last series of British escape maps are based on Survey of India maps. The Survey of India was established in 1767 by British East Indies Company to fulfill the survey and map needs of the British Empire of India. Some of these maps are readily identified by the marking on the maps "Heliozincographed at the E Survey of India Offices." The maps were printed on silk with a grayish background, and it has been reported that there are eleven known sheets. They are primarily black and white, although occasionally accompanied by blue and sometimes red colors. The maps can be identified by the following sample designations:

Survey of India Map

Survey of India Map

Records of MIS-X Washington reveal that in May 1944, 100,000 yards of map cloth were shipped to MIS-X India. [39] Perhaps this cloth was used in the production of some of the Survey of India maps. MI 9's advance base in New Delhi, India, distributed the maps[40] although some of the cloth maps produced by the Survey of India covered China and were issued by MIS-X China to pilots flying the Hump.[41] (Click here for a list of the Survey of India maps and sample photos.)

Interesting Survey of India Orange Cloth Map (probably for nighttime use)

Not counting the Survey of India maps, all and all, it has been estimated that over 1 million copies of over 250 escape maps were made during Worlds War II by the British.[42] Records of MIS-X (ETO) show that over 300,000 cloth maps were furnished by the British under the Lend-Lease Act for US requirements in the European theater alone, each map was valued in 1945 at $1.01.[43] At the conclusion of the war in Europe, all silk maps were declassified from Restricted and recipients were permitted to retain them as souvenirs.[44] Also, there are reported accounts of large quantities of unissued cloth maps being released for sale to the public decades after the war ended. How useful were the maps? According to an MIS-X USETO bulletin, an analysis up to July 1944 revealed that out of a survey of 772 of USAAF officers and enlisted men whose aircraft were downed, 322 stated they had used their maps. This was reported as the second most used item in their escape and evasion kits, second only to the use of money.[45] [1] Clayton Hutton, Official Secrets, Crown Publishers, New York 1961.

[2] Clayton Hutton, Official Secrets, Crown Publishers, New York 1961, pp. 3-7.

[3] Clayton Hutton, Official Secrets, Crown Publishers, New York 1961, p. 8.

[4] M.R.D. Foot and J.M. Langley, MI 9 Escape and Evasion 1939-1945, Book Club Associates, London 1979, p. 39.

[5] Direction from Secretary of War, approved October 6, 1942 (Secret).

[6] MIS-X Manual, Asiatic-Pacific Theater chapter, p. 2 (Secret).

[7] MIS-X Manual, Asiatic-Pacific Theater chapter, p. 2 (Secret).

[8] Outgoing Message from MIS POW Branch to CG US Forces in NATO, Number 9429 June 1, 1943 (Secret).

[9] Paraphrase of Cipher Message from War Office DDMI(P/W) to India, 2228 IN, undated (Secret).

[10] Paraphrase of Cipher Message from War Office DDMI(P/W) to India, 2228 IN, undated (Secret).

[11] MIS-X Manual, Asiatic-Pacific Theater chapter, p. 2 (Secret).

[12] MIS-X Manual, Asiatic-Pacific Theater chapter, p. 2 (Secret).

[13] MIS-X Manual, Asiatic-Pacific Theater chapter, p. 2 (Secret).

[14] Outgoing Message from MIS POW Branch to CINC SWPA, Number 4379, May 31, 1943 (Secret).

[15] Outgoing Message from MIS POW Branch to CINC SWPA, Number 4379, May 31, 1943 (Secret).

[16] Outgoing Message from MID Policy Group II to Commanding General USAF Pacific Oceans Area, Number WAR 31519, September 15, 1944 (Secret).

[17] Paraphrase of Cipher Message from War Office DDMI(P/W) to India, 2228 IN, undated (Secret).

[18] MIS-X Manual, Asiatic-Pacific Theater chapter, p. 2 (Secret).

[19] MIS-X Manual, Asiatic-Pacific Theater chapter, p. 2 (Secret).

[20] MIS-X Manual, Asiatic-Pacific Theater chapter, p. 2 (Secret).

[21] MI 9's official charter stated: The section is responsible for: (a) The preparation and execution of plans for facilitating the escape of British Prisoners of War of all three Services in Germany or elsewhere. (b) Arranging instruction in connection with above. (c) Making other advance provision as considered necessary. (d) Collection and dissemination of information obtained from British Prisoners of War. (e) Advising on counter-escape measures for German Prisoners of War in Great Britain, if requested to do so. Per Ardua Libertas, 1942 (a 67 page booklet produced by MI 9 setting forth escape and evasion aids produced during WWII and included sample copies of some of the silk escape maps; copies of the booklet were given to American intelligence officers when they visited MI 9 in 1942.); see also M.R.D. Foot and J.M. Langley, MI 9 Escape and Evasion 1939-1945, Book Club Associates, London 1979, pp. 34-38.

[22] Clayton Hutton, Official Secrets, Crown Publishers, New York 1961, p. 9.

[23] Clayton Hutton, Official Secrets, Crown Publishers, New York 1961, pp. 18-20.

[24] Clayton Hutton, Official Secrets, Crown Publishers, New York 1961, pp. 21-24.

[25] Clayton Hutton, Official Secrets, Crown Publishers, New York 1961, p. 24.

[26] Notes for Escapers and Evaders, MI9, undated but from context early in WWII (Secret).

[27] Much of the information regarding British escape maps was derived from Barbara A. Bond, "Silk Maps: The story of MI9's excursion into the world of cartography 1939-1945," Cartographic Journal, Vol. 21, No. 2 Dec 1984, pp. 141-43 and Barbara Bond, "Maps Printed on Silk," The Map Collector, No. 22, Mar 1983, p. 13.

[28] Per Ardua Libertas, 1942 (a 67 page booklet produced by MI 9 setting forth escape and evasion aids produced during WWII and included sample copies of some of the silk escape maps; copies of the booklet were given to American intelligence officers when they visited MI9 in 1942.).

[29] Clayton Hutton, Official Secrets, Crown Publishers, New York 1961, pp. 24-27.

[30] Clayton Hutton, Official Secrets, Crown Publishers, New York 1961, p. 61.

[31] Letter from Brigadier B.P.T. O'Brien (British Joint Staff Mission Washington) to Col. John E. Johnston (MIS-X), 14 April 1945 (Restricted).

[32] Barbara A. Bond, "Silk Maps: The story of MI9's excursion into the world of cartography 1939-1945," Cartographic Journal, Vol. 21, No. 2 Dec 1984, p. 142; Barbara Bond, "Maps Printed on Silk," The Map Collector, No. 22, Mar 1983, p. 13.

[33] Memo from Col. Catesby ap C. Jones (MIS POW Branch) to Brigadier General B.W. Chidlaw (Assistant Chief of Air Staff, Material, Maintenance and Distribution), Subject Request for Parachute Reject Silk, 6 March 1944; Paraphrase of Message from MILID to Military Attache London, M.A. London 12475, April 5, 1944 (Secret); MIS-X Technical Section, War Diary for August and September 1945, prepared by Major Leo H. Crosson, 8 October 1945 (Secret).

[33a] Equipment on Operation, Bulletin No.3 (amended July 22, 1944), Headquarters, European Theater of Operations, P/W and X Detachment, Military Intelligence Service (Secret); Sumary of Report Under Reciprocal Aid, Headquarters, European Theater of Operations, P/W and X Detachment, Military Intelligence Service, June 30, 1945.

[33b] Memo from Major Irvin H. Luiten, Headquarters, European Theater of Operations, Det. C, P/W and X Detachment, Military Intelligence Service, APO 413, to IS9 (z) (attn: S/Ldr Whitehead), Subject: Equipment Requirements, March 12, 1945.

[34] GSI(e) Progress Report No. 8 from Lt. Col. A. Boyes Cooper to Brigadier N.R. Crockatt, January 8, 1944 (Most Secret).

[35] E Group was MI 9's advance base operating in New Delhi, India.

[36] Eastern Fleet E Bulletin, C.B. 04373/44 (S).

[37] Barbara A. Bond, Silk Maps: The story of MI9's excursion into the world of cartography 1939-1945, Cartographic Journal, Vol. 21, No. 2 Dec 1984, pp. 142-43.

[38] Barbara A. Bond, "Silk Maps: The story of MI9's excursion into the world of cartography 1939-1945," Cartographic Journal, Vol. 21, No. 2 Dec 1984, p 143; Barbara Bond, "Maps Printed on Silk, The Map Collector," No. 22, Mar 1983, p. 13.

[39] Memorandum to Major A.R. Wichtrich, MIS-X China from Colonel Russell H. Sweet, MIS-X Washington, June 8, 1944, Subject: Status of Requests from CBI Theaters and Shipping Information (Secret).

[40] M.R.D. Foot and J.M. Langley, MI 9 Escape and Evasion 1939-1945, Book Club Associates, London 1979, p. 247. [41] Memorandum from AGAS-China to All Field Units, August 4, 1944, Subject AGAS Operations) (citing the issuance of 50 cloth maps of Shanghai) (TS); Memorandum to MIS-X Washington from MIS-X China, undated (requests copies of silk maps that MIS-X Washington is in process of producing so MIS-X China can compare them with the silk maps produced by the British in India (Secret).

[42] Barbara A. Bond, "Silk Maps: The story of MI9's excursion into the world of cartography 1939-1945," Cartographic Journal, Vol. 21, No. 2 Dec 1984, p. 141; Barbara Bond, "Maps Printed on Silk," The Map Collector, No. 22, Mar 1983, p. 11.

[43] MIS Summary Report under Reciprocal Aid, 1 Jun-31 Mar 1945. Previous reports indicated that the maps were valued at $2.20 each.

[44] Memo from Major R.G. Sillars (MI 9), Subject: Aids To Escape, June 2, 1945.

[45] MIS-X USETO Security-Evasion-Escape Bulletin No. 3, Equipment on Operations, July 15, 1944 (Secret). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

© Copyright 2008. All rights reserved. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||